Harry Stoner wakes up screaming.

For the next 24 hours we will follow him as cajoles, begs, and pleads with the people around him on a critical day for the life of his clothing company.

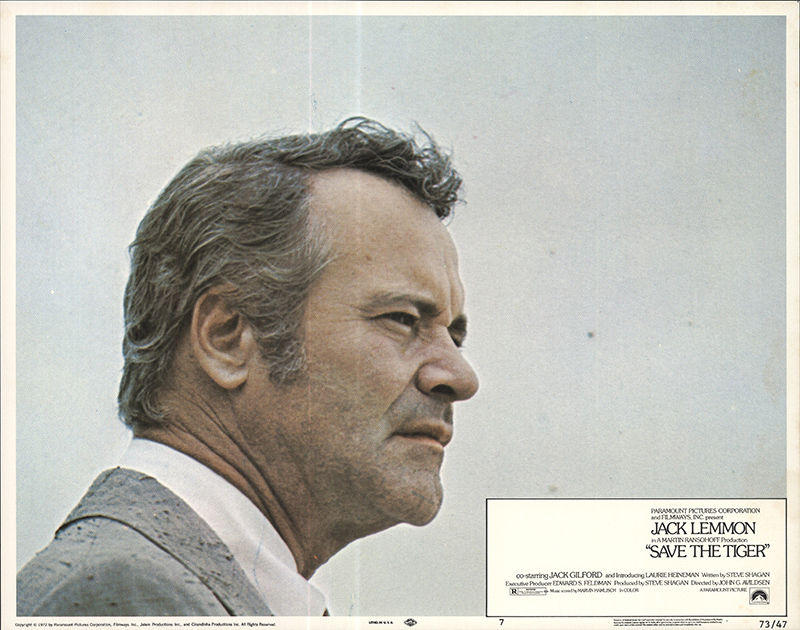

Stoner (Jack Lemmon) has achieved the American dream, a successful business (as long as the IRS doesn’t look too close), a happy marriage (as long she doesn’t look too close), with a big house, a fancy car, a maid and a daughter in a European boarding school.

“I miss the kid,” Stoner says in one of the many complaints he will make about his life.

Stoner is upset at how hard it is to make a semi-honest buck, how America has changed in some undefinable way (it has to do with how hippie kids are just giving sex away, how banks won’t loan out money like they used to and professional ball players used to be tough guys and now they are all wimps.

I’m not sure they understood PTSD in 1973 but the World War 2 veteran is also clearly going through an episode. In another complaint he points out that the beaches of Normandy where so many boys gave their lives are now filled with vacationers wearing bikinis.

Stoner spends his day having what looks like familiar arguments with his wife and his co-workers. Jack Gilford turns in another of his great crusty performances as Stoner’s accountant and business partner.

Before we meet him Stoner tells his wife that Phil Greene (Gilford) is worried about the business.

“He’s always worried,” she replies.

And indeed he is. But it’s clear that the business is only half of his concern, his other headache is Stoner who has not yet met a line he won’t cross to make the business succeed.

You would give up on all this, if it were coming from a different actor, but from Jack Lemmon it’s something close to poetry.

Lemmon used his star power and two years of his own cajoling to get Save The Tiger made. He performed in the movie for scale after the studio gave them a tiny budget ($1 million) and a shot. He was rewarded with his second Oscar and one of those performances that stands the test of time.

Great actors know which roles will work for them and this war vet in the midst of an emotional and moral decline is the perfect Lemmon vehicle.

I watched this movie fifty years after it was released and it is has lost none of its power. Even its concerns remain. Apparently, a movie about an America in decline will always be relevant.

Spoilers below:

The moral question of the story is whether or not Stoner will hire an arsonist. If he burns down one of his factories he can have what he really wants (the money he needs to fund one more season).

Now, naturally I assumed that the arsonist (Thayer David) would return with news that the arson went bad and someone died.

But the screenplay is too smart for that. Instead, the arsonist does return and Stoner makes a choice that sells the last bit of his soul away.

None of this is heavy handed. There is no denouement where a judge or a cop points a crooked finger at Stoner and shouts, “Crime does not pay.”

Stoner is surely doomed but what form that doom will ultimately take is left up to the viewer to imagine.

As the movie took its final few turns I kept thinking about tigers. And how, so few of them exist in the wild.

The ones who survive live in cages.

Leave a comment